The Four Vedas In Pdf

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

Divisions |

Rig vedic Sama vedic Yajur vedic Atharva vedic |

| Related Hindu texts |

Brahma puranas Vaishnava puranas Shaiva puranas |

The Upanishads (/uːˈpænɪˌʃædz, uːˈpɑːnɪˌʃɑːdz/;[1]Sanskrit: उपनिषद्Upaniṣad[ʊpɐnɪʂɐd]), a part of the Vedas, are ancient Sanskrit texts that contain some of the central philosophical concepts and ideas of Hinduism, some of which are shared with religious traditions like Buddhism and Jainism.[2][3][note 1][note 2] Among the most important literature in the history of Indian religions and culture, the Upanishads played an important role in the development of spiritual ideas in ancient India, marking a transition from Vedic ritualism to new ideas and institutions.[6] Of all Vedic literature, the Upanishads alone are widely known, and their central ideas are at the spiritual core of Hindus.[2][7]

All Four Vedas In Hindi Pdf

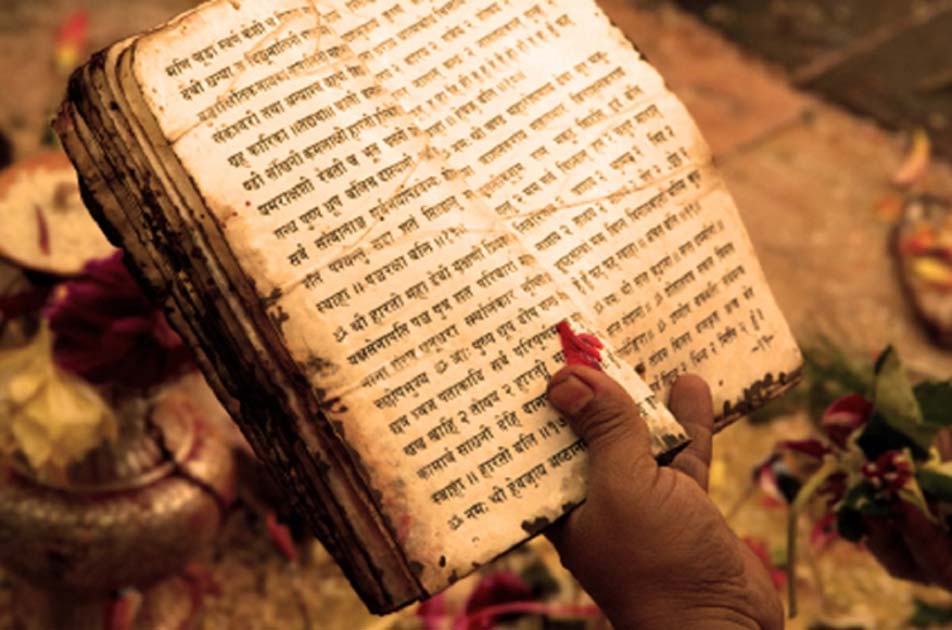

The below four Vedas in english are considered to be having the most significance in Hindu religion and literature. These are a large body of text originated from the ancient Vedic Granth. Veda means knowledge in Sanskrit which is derived from the root word ‘Vid’. There are four texts that compose the Vedas: Rig-Veda, Sama-Veda, Yajur-Veda and Atharva-Veda. The Rig – Veda is the oldest, dating back to 1500 B.C.E., and is the most revered and important of the four. The Rig-Veda’s collection of inspired hymns and mantras were used to invoke courage, happiness, health, peace, prosperity.

The Upanishads are commonly referred to as Vedānta. Vedanta has been interpreted as the 'last chapters, parts of the Veda' and alternatively as 'object, the highest purpose of the Veda'.[8] The concepts of Brahman (ultimate reality) and Ātman (soul, self) are central ideas in all of the Upanishads,[9][10] and 'know that you are the Ātman' is their thematic focus.[10][11] Along with the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahmasutra, the mukhya Upanishads (known collectively as the Prasthanatrayi)[12] provide a foundation for the several later schools of Vedanta, among them, two influential monistic schools of Hinduism.[note 3][note 4][note 5]

More than 200 Upanishads are known, of which the first dozen or so are the oldest and most important and are referred to as the principal or main (mukhya) Upanishads.[15][16] The mukhya Upanishads are found mostly in the concluding part of the Brahmanas and Aranyakas[17] and were, for centuries, memorized by each generation and passed down orally. The early Upanishads all predate the Common Era, five[note 6] of them in all likelihood pre-Buddhist (6th century BCE),[18] down to the Maurya period.[19] Of the remainder, 95 Upanishads are part of the Muktika canon, composed from about the last centuries of 1st-millennium BCE through about 15th-century CE.[20][21] New Upanishads, beyond the 108 in the Muktika canon, continued to be composed through the early modern and modern era,[22] though often dealing with subjects which are unconnected to the Vedas.[23]

With the translation of the Upanishads in the early 19th century they also started to attract attention from a western audience. Arthur Schopenhauer was deeply impressed by the Upanishads and called it 'the production of the highest human wisdom'.[24] Modern era Indologists have discussed the similarities between the fundamental concepts in the Upanishads and major western philosophers.[25][26][27]

- 2Development

- 3Classification

- 5Philosophy

- 6Schools of Vedanta

Etymology[edit]

The Sanskrit term Upaniṣad (from upa 'by' and ni-ṣad 'sit down')[28] translates to 'sitting down near', referring to the student sitting down near the teacher while receiving spiritual knowledge.[29] Other dictionary meanings include 'esoteric doctrine' and 'secret doctrine'. Monier-Williams' Sanskrit Dictionary notes – 'According to native authorities, Upanishad means setting to rest ignorance by revealing the knowledge of the supreme spirit.'[30]

Adi Shankaracharya explains in his commentary on the Kaṭha and Brihadaranyaka Upanishad that the word means Ātmavidyā, that is, 'knowledge of the self', or Brahmavidyā 'knowledge of Brahma'. The word appears in the verses of many Upanishads, such as the fourth verse of the 13th volume in first chapter of the Chandogya Upanishad. Max Müller as well as Paul Deussen translate the word Upanishad in these verses as 'secret doctrine',[31][32] Robert Hume translates it as 'mystic meaning',[33] while Patrick Olivelle translates it as 'hidden connections'.[34]

Development[edit]

Authorship[edit]

The authorship of most Upanishads is uncertain and unknown. Radhakrishnan states, 'almost all the early literature of India was anonymous, we do not know the names of the authors of the Upanishads'.[35] The ancient Upanishads are embedded in the Vedas, the oldest of Hinduism's religious scriptures, which some traditionally consider to be apauruṣeya, which means 'not of a man, superhuman'[36] and 'impersonal, authorless'.[37][38][39] The Vedic texts assert that they were skillfully created by Rishis (sages), after inspired creativity, just as a carpenter builds a chariot.[40] One of the Upanishads, the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, was said to have been organized by King Shiradhaj Janaka in the Ramayana. It was a gathering of rishis from all across Aryavarta to share their knowledge of the Vedas to expand the knowledge of humanity.[41]

The various philosophical theories in the early Upanishads have been attributed to famous sages such as Yajnavalkya, Uddalaka Aruni, Shvetaketu, Shandilya, Aitareya, Balaki, Pippalada, and Sanatkumara.[35][42] Women, such as Maitreyi and Gargi participate in the dialogues and are also credited in the early Upanishads.[43] There are some exceptions to the anonymous tradition of the Upanishads. The Shvetashvatara Upanishad, for example, includes closing credits to sage Shvetashvatara, and he is considered the author of the Upanishad.[44]

Many scholars believe that early Upanishads were interpolated[45] and expanded over time. There are differences within manuscripts of the same Upanishad discovered in different parts of South Asia, differences in non-Sanskrit version of the texts that have survived, and differences within each text in terms of meter,[46] style, grammar and structure.[47][48] The existing texts are believed to be the work of many authors.[49].

Chronology[edit]

Scholars are uncertain about when the Upanishads were composed.[50] The chronology of the early Upanishads is difficult to resolve, states philosopher and Sanskritist Stephen Phillips,[15] because all opinions rest on scanty evidence and analysis of archaism, style and repetitions across texts, and are driven by assumptions about likely evolution of ideas, and presumptions about which philosophy might have influenced which other Indian philosophies. Indologist Patrick Olivelle says that 'in spite of claims made by some, in reality, any dating of these documents [early Upanishads] that attempts a precision closer than a few centuries is as stable as a house of cards'.[18] Some scholars have tried to analyse similarities between Hindu Upanishads and Buddhist literature to establish chronology for the Upanishads.[19]

Patrick Olivelle gives the following chronology for the early Upanishads, also called the Principal Upanishads:[50][18]

- The Brhadaranyaka and the Chandogya are the two earliest Upanishads. They are edited texts, some of whose sources are much older than others. The two texts are pre-Buddhist; they may be placed in the 7th to 6th centuries BCE, give or take a century or so.[51][19]

- The three other early prose Upanisads—Taittiriya, Aitareya, and Kausitaki come next; all are probably pre-Buddhist and can be assigned to the 6th to 5th centuries BCE.

- The Kena is the oldest of the verse Upanisads followed by probably the Katha, Isa, Svetasvatara, and Mundaka. All these Upanisads were composed probably in the last few centuries BCE.[52]

- The two late prose Upanisads, the Prasna and the Mandukya, cannot be much older than the beginning of the common era.[50][18]

Stephen Phillips places the early Upanishads in the 800 to 300 BCE range. He summarizes the current Indological opinion to be that the Brhadaranyaka, Chandogya, Isha, Taittiriya, Aitareya, Kena, Katha, Mundaka, and Prasna Upanishads are all pre-Buddhist and pre-Jain, while Svetasvatara and Mandukya overlap with the earliest Buddhist and Jain literature.[15]

The later Upanishads, numbering about 95, also called minor Upanishads, are dated from the late 1st-millennium BCE to mid 2nd-millennium CE.[20]Gavin Flood dates many of the twenty Yoga Upanishads to be probably from the 100 BCE to 300 CE period.[21]Patrick Olivelle and other scholars date seven of the twenty Sannyasa Upanishads to likely have been complete sometime between the last centuries of the 1st-millennium BCE to 300 CE.[20] About half of the Sannyasa Upanishads were likely composed in 14th- to 15th-century CE.[20]

Geography[edit]

The general area of the composition of the early Upanishads is considered as northern India. The region is bounded on the west by the upper Indus valley, on the east by lower Ganges region, on the north by the Himalayan foothills, and on the south by the Vindhya mountain range.[18] Scholars are reasonably sure that the early Upanishads were produced at the geographical center of ancient Brahmanism, comprising the regions of Kuru-Panchala and Kosala-Videha together with the areas immediately to the south and west of these.[53] This region covers modern Bihar, Nepal, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, eastern Rajasthan, and northern Madhya Pradesh.[18]

While significant attempts have been made recently to identify the exact locations of the individual Upanishads, the results are tentative. Witzel identifies the center of activity in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad as the area of Videha, whose king, Janaka, features prominently in the Upanishad.[54] The Chandogya Upanishad was probably composed in a more western than eastern location in the Indian subcontinent, possibly somewhere in the western region of the Kuru-Panchala country.[55]

Compared to the Principal Upanishads, the new Upanishads recorded in the Muktikā belong to an entirely different region, probably southern India, and are considerably relatively recent.[56] In the fourth chapter of the Kaushitaki Upanishad, a location named Kashi (modern Varanasi) is mentioned.[18]

Classification[edit]

Muktika canon: major and minor Upanishads[edit]

There are more than 200 known Upanishads, one of which, the Muktikā Upanishad, predates 1656 CE[57] and contains a list of 108 canonical Upanishads,[58] including itself as the last. These are further divided into Upanishads associated with Shaktism (goddess Shakti), Sannyasa (renunciation, monastic life), Shaivism (god Shiva), Vaishnavism (god Vishnu), Yoga, and Sāmānya (general, sometimes referred to as Samanya-Vedanta).[59][60]

Some of the Upanishads are categorized as 'sectarian' since they present their ideas through a particular god or goddess of a specific Hindu tradition such as Vishnu, Shiva, Shakti, or a combination of these such as the Skanda Upanishad. These traditions sought to link their texts as Vedic, by asserting their texts to be an Upanishad, thereby a Śruti.[61] Most of these sectarian Upanishads, for example the Rudrahridaya Upanishad and the Mahanarayana Upanishad, assert that all the Hindu gods and goddesses are the same, all an aspect and manifestation of Brahman, the Vedic concept for metaphysical ultimate reality before and after the creation of the Universe.[62][63]

Mukhya Upanishads[edit]

The Mukhya Upanishads can be grouped into periods. Of the early periods are the Brihadaranyaka and the Chandogya, the oldest.[64][note 7]

The Aitareya, Kauṣītaki and Taittirīya Upanishads may date to as early as the mid 1st millennium BCE, while the remnant date from between roughly the 4th to 1st centuries BCE, roughly contemporary with the earliest portions of the Sanskrit epics.One chronology assumes that the Aitareya, Taittiriya, Kausitaki, Mundaka, Prasna, and Katha Upanishads has Buddha's influence, and is consequently placed after the 5th century BCE, while another proposal questions this assumption and dates it independent of Buddha's date of birth. After these Principal Upanishads are typically placed the Kena, Mandukya and Isa Upanishads, but other scholars date these differently.[19] Not much is known about the authors except for those, like Yajnavalkayva and Uddalaka, mentioned in the texts.[17] A few women discussants, such as Gargi and Maitreyi, the wife of Yajnavalkayva,[66] also feature occasionally.

Each of the principal Upanishads can be associated with one of the schools of exegesis of the four Vedas (shakhas).[67] Many Shakhas are said to have existed, of which only a few remain. The new Upanishads often have little relation to the Vedic corpus and have not been cited or commented upon by any great Vedanta philosopher: their language differs from that of the classic Upanishads, being less subtle and more formalized. As a result, they are not difficult to comprehend for the modern reader.[68]

| Veda | Recension | Shakha | Principal Upanishad |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rig Veda | Only one recension | Shakala | Aitareya |

| Sama Veda | Only one recension | Kauthuma | Chāndogya |

| Jaiminiya | Kena | ||

| Ranayaniya | |||

| Yajur Veda | Krishna Yajur Veda | Katha | Kaṭha |

| Taittiriya | Taittirīya and Śvetāśvatara[69] | ||

| Maitrayani | Maitrāyaṇi | ||

| Hiranyakeshi (Kapishthala) | |||

| Kathaka | |||

| Shukla Yajur Veda | Vajasaneyi Madhyandina | Isha and Bṛhadāraṇyaka | |

| Kanva Shakha | |||

| Atharva | Two recensions | Shaunaka | Māṇḍūkya and Muṇḍaka |

| Paippalada | Prashna Upanishad |

The Kauśītāki and Maitrāyaṇi Upanishads are sometimes added to the list of the mukhya Upanishads.

New Upanishads[edit]

There is no fixed list of the Upanishads as newer ones, beyond the Muktika anthology of 108 Upanishads, have continued to be discovered and composed.[70] In 1908, for example, four previously unknown Upanishads were discovered in newly found manuscripts, and these were named Bashkala, Chhagaleya, Arsheya, and Saunaka, by Friedrich Schrader,[71] who attributed them to the first prose period of the Upanishads.[72] The text of three of them, namely the Chhagaleya, Arsheya, and Saunaka, were incomplete and inconsistent, likely poorly maintained or corrupted.[72]

Ancient Upanishads have long enjoyed a revered position in Hindu traditions, and authors of numerous sectarian texts have tried to benefit from this reputation by naming their texts as Upanishads.[73] These 'new Upanishads' number in the hundreds, cover diverse range of topics from physiology[74] to renunciation[75] to sectarian theories.[73] They were composed between the last centuries of the 1st millennium BCE through the early modern era (~1600 CE).[73][75] While over two dozen of the minor Upanishads are dated to pre-3rd century CE,[20][21] many of these new texts under the title of 'Upanishads' originated in the first half of the 2nd millennium CE,[73] they are not Vedic texts, and some do not deal with themes found in the Vedic Upanishads.[23]

The main Shakta Upanishads, for example, mostly discuss doctrinal and interpretative differences between the two principal sects of a major Tantric form of Shaktism called Shri Vidyaupasana. The many extant lists of authentic Shakta Upaniṣads vary, reflecting the sect of their compilers, so that they yield no evidence of their 'location' in Tantric tradition, impeding correct interpretation. The Tantra content of these texts also weaken its identity as an Upaniṣad for non-Tantrikas. Sectarian texts such as these do not enjoy status as shruti and thus the authority of the new Upanishads as scripture is not accepted in Hinduism.[76]

Association with Vedas[edit]

All Upanishads are associated with one of the four Vedas—Rigveda, Samaveda, Yajurveda (there are two primary versions or Samhitas of the Yajurveda: Shukla Yajurveda, Krishna Yajurveda), and Atharvaveda.[77] During the modern era, the ancient Upanishads that were embedded texts in the Vedas, were detached from the Brahmana and Aranyaka layers of Vedic text, compiled into separate texts and these were then gathered into anthologies of Upanishads.[73] These lists associated each Upanishad with one of the four Vedas, many such lists exist, and these lists are inconsistent across India in terms of which Upanishads are included and how the newer Upanishads are assigned to the ancient Vedas. In south India, the collected list based on Muktika Upanishad,[note 8] and published in Telugu language, became the most common by the 19th-century and this is a list of 108 Upanishads.[73][78] In north India, a list of 52 Upanishads has been most common.[73]

The Muktikā Upanishad's list of 108 Upanishads groups the first 13 as mukhya,[79][note 9] 21 as Sāmānya Vedānta, 20 as Sannyāsa,[83] 14 as Vaishnava, 12 as Shaiva, 8 as Shakta, and 20 as Yoga.[84] The 108 Upanishads as recorded in the Muktikā are shown in the table below.[77] The mukhya Upanishads are the most important and highlighted.[81]

| Veda | Number[77] | Mukhya[79] | Sāmānya | Sannyāsa[83] | Śākta[85] | Vaiṣṇava[86] | Śaiva[87] | Yoga[84] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ṛigveda | 10 | Aitareya, Kauśītāki | Ātmabodha, Mudgala | Nirvāṇa | Tripura, Saubhāgya-lakshmi, Bahvṛca | - | Akṣamālika | Nādabindu |

| Samaveda | 16 | Chāndogya, Kena | Vajrasūchi, Maha, Sāvitrī | Āruṇi, Maitreya, Brhat-Sannyāsa, Kuṇḍika (Laghu-Sannyāsa) | - | Vāsudeva, Avyakta | Rudrākṣa, Jābāli | Yogachūḍāmaṇi, Darśana |

| Krishna Yajurveda | 32 | Taittiriya, Katha, Śvetāśvatara, Maitrāyaṇi[note 10] | Sarvasāra, Śukarahasya, Skanda, Garbha, Śārīraka, Ekākṣara, Akṣi | Brahma, (Laghu, Brhad) Avadhūta, Kaṭhasruti | Sarasvatī-rahasya | Nārāyaṇa, Kali-Saṇṭāraṇa | Kaivalya, Kālāgnirudra, Dakṣiṇāmūrti, Rudrahṛdaya, Pañcabrahma | Amṛtabindu, Tejobindu, Amṛtanāda, Kṣurika, Dhyānabindu, Brahmavidyā, Yogatattva, Yogaśikhā, Yogakuṇḍalini, Varāha |

| Shukla Yajurveda | 19 | Bṛhadāraṇyaka, Īśa | Subala, Mantrika, Niralamba, Paingala, Adhyatma, Muktika | Jābāla, Paramahaṃsa, Bhikṣuka, Turīyātītavadhuta, Yājñavalkya, Śāṭyāyaniya | - | Tārasāra | - | Advayatāraka, Haṃsa, Triśikhi, Maṇḍalabrāhmaṇa |

| Atharvaveda | 31 | Muṇḍaka, Māṇḍūkya, Praśna | Ātmā, Sūrya, Prāṇāgnihotra[89] | Āśrama, Nārada-parivrājaka, Paramahaṃsa parivrājaka, Parabrahma | Sītā, Devī, Tripurātapini, Bhāvana | Nṛsiṃhatāpanī, Mahānārāyaṇa (Tripād vibhuti), Rāmarahasya, Rāmatāpaṇi, Gopālatāpani, Kṛṣṇa, Hayagrīva, Dattātreya, Gāruḍa | Atharvasiras,[90]Atharvaśikha, Bṛhajjābāla, Śarabha, Bhasma, Gaṇapati | Śāṇḍilya, Pāśupata, Mahāvākya |

| Total Upanishads | 108 | 13[note 9] | 21 | 19 | 8 | 14 | 13 | 20 |

Philosophy[edit]

The Upanishadic age was characterized by a pluralism of worldviews. While some Upanishads have been deemed 'monistic', others, including the Katha Upanishad, are dualistic.[91] The Maitri is one of the Upanishads that inclines more toward dualism, thus grounding classical Samkhya and Yoga schools of Hinduism, in contrast to the non-dualistic Upanishads at the foundation of its Vedanta school.[92] They contain a plurality of ideas.[93][note 11]

Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan states that the Upanishads have dominated Indian philosophy, religion and life ever since their appearance.[94] The Upanishads are respected not because they are considered revealed (Shruti), but because they present spiritual ideas that are inspiring.[95] The Upanishads are treatises on Brahman-knowledge, that is knowledge of Ultimate Hidden Reality, and their presentation of philosophy presumes, 'it is by a strictly personal effort that one can reach the truth'.[96] In the Upanishads, states Radhakrishnan, knowledge is a means to freedom, and philosophy is the pursuit of wisdom by a way of life.[97]

The Upanishads include sections on philosophical theories that have been at the foundation of Indian traditions. For example, the Chandogya Upanishad includes one of the earliest known declaration of Ahimsa (non-violence) as an ethical precept.[98][99] Discussion of other ethical premises such as Damah (temperance, self-restraint), Satya (truthfulness), Dāna (charity), Ārjava (non-hypocrisy), Daya (compassion) and others are found in the oldest Upanishads and many later Upanishads.[100][101] Similarly, the Karma doctrine is presented in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, which is the oldest Upanishad.[102]

Development of thought[edit]

| Part of a series on | ||||||||||||||

| Hindu philosophy | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthodox | ||||||||||||||

| Heterodox | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

While the hymns of the Vedas emphasize rituals and the Brahmanas serve as a liturgical manual for those Vedic rituals, the spirit of the Upanishads is inherently opposed to ritual.[103] The older Upanishads launch attacks of increasing intensity on the ritual. Anyone who worships a divinity other than the self is called a domestic animal of the gods in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. The Chāndogya Upanishad parodies those who indulge in the acts of sacrifice by comparing them with a procession of dogs chanting Om! Let's eat. Om! Let's drink.[103]

The Kaushitaki Upanishad asserts that 'external rituals such as Agnihotram offered in the morning and in the evening, must be replaced with inner Agnihotram, the ritual of introspection', and that 'not rituals, but knowledge should be one's pursuit'.[104] The Mundaka Upanishad declares how man has been called upon, promised benefits for, scared unto and misled into performing sacrifices, oblations and pious works.[105] Mundaka thereafter asserts this is foolish and frail, by those who encourage it and those who follow it, because it makes no difference to man's current life and after-life, it is like blind men leading the blind, it is a mark of conceit and vain knowledge, ignorant inertia like that of children, a futile useless practice.[105][106] The Maitri Upanishad states,[107]

The performance of all the sacrifices, described in the Maitrayana-Brahmana, is to lead up in the end to a knowledge of Brahman, to prepare a man for meditation. Therefore, let such man, after he has laid those fires,[108] meditate on the Self, to become complete and perfect.

The opposition to the ritual is not explicit in the oldest Upanishads. On occasions, the Upanishads extend the task of the Aranyakas by making the ritual allegorical and giving it a philosophical meaning. For example, the Brihadaranyaka interprets the practice of horse-sacrifice or ashvamedha allegorically. It states that the over-lordship of the earth may be acquired by sacrificing a horse. It then goes on to say that spiritual autonomy can only be achieved by renouncing the universe which is conceived in the image of a horse.[103]

In similar fashion, Vedic gods such as the Agni, Aditya, Indra, Rudra, Visnu, Brahma, and others become equated in the Upanishads to the supreme, immortal, and incorporeal Brahman-Atman of the Upanishads, god becomes synonymous with self, and is declared to be everywhere, inmost being of each human being and within every living creature.[111][112][113] The one reality or ekam sat of the Vedas becomes the ekam eva advitiyam or 'the one and only and sans a second' in the Upanishads.[103] Brahman-Atman and self-realization develops, in the Upanishad, as the means to moksha (liberation; freedom in this life or after-life).[113][114][115]

According to Jayatilleke, the thinkers of Upanishadic texts can be grouped into two categories.[116] One group, which includes early Upanishads along with some middle and late Upanishads, were composed by metaphysicians who used rational arguments and empirical experience to formulate their speculations and philosophical premises. The second group includes many middle and later Upanishads, where their authors professed theories based on yoga and personal experiences.[116] Yoga philosophy and practice, adds Jayatilleke, is 'not entirely absent in the Early Upanishads'.[116] The development of thought in these Upanishadic theories contrasted with Buddhism, since the Upanishadic inquiry assumed there is a soul (Atman), while Buddhism assumed there is no soul (Anatta), states Jayatilleke.[117]

Brahman and Atman[edit]

Two concepts that are of paramount importance in the Upanishads are Brahman and Atman.[9] The Brahman is the ultimate reality and the Atman is individual self (soul).[118][119] Brahman is the material, efficient, formal and final cause of all that exists.[120][121][122] It is the pervasive, genderless, infinite, eternal truth and bliss which does not change, yet is the cause of all changes.[118][123] Brahman is 'the infinite source, fabric, core and destiny of all existence, both manifested and unmanifested, the formless infinite substratum and from which the universe has grown'. Brahman in Hinduism, states Paul Deussen, as the 'creative principle which lies realized in the whole world'.[124]

The word Atman means the inner self, the soul, the immortal spirit in an individual, and all living beings including animals and trees.[125][119] Ātman is a central idea in all the Upanishads, and 'Know your Ātman' their thematic focus.[10] These texts state that the inmost core of every person is not the body, nor the mind, nor the ego, but Atman – 'soul' or 'self'.[126] Atman is the spiritual essence in all creatures, their real innermost essential being.[127][128] It is eternal, it is ageless. Atman is that which one is at the deepest level of one's existence.

Atman is the predominantly discussed topic in the Upanishads, but they express two distinct, somewhat divergent themes. Younger upanishads state that Brahman (Highest Reality, Universal Principle, Being-Consciousness-Bliss) is identical with Atman, while older upanishads state Atman is part of Brahman but not identical.[129][130] The Brahmasutra by Badarayana (~ 100 BCE) synthesized and unified these somewhat conflicting theories. According to Nakamura, the Brahman sutras see Atman and Brahman as both different and not-different, a point of view which came to be called bhedabheda in later times.[131] According to Koller, the Brahman sutras state that Atman and Brahman are different in some respects particularly during the state of ignorance, but at the deepest level and in the state of self-realization, Atman and Brahman are identical, non-different.[129] This ancient debate flowered into various dual, non-dual theories in Hinduism.

Reality and Maya[edit]

Two different types of the non-dual Brahman-Atman are presented in the Upanishads, according to Mahadevan. The one in which the non-dual Brahman-Atman is the all inclusive ground of the universe and another in which empirical, changing reality is an appearance (Maya).[132]

The Upanishads describe the universe, and the human experience, as an interplay of Purusha (the eternal, unchanging principles, consciousness) and Prakṛti (the temporary, changing material world, nature).[133] The former manifests itself as Ātman (soul, self), and the latter as Māyā. The Upanishads refer to the knowledge of Atman as 'true knowledge' (Vidya), and the knowledge of Maya as 'not true knowledge' (Avidya, Nescience, lack of awareness, lack of true knowledge).[134]

Hendrick Vroom explains, 'the term Maya [in the Upanishads] has been translated as 'illusion,' but then it does not concern normal illusion. Here 'illusion' does not mean that the world is not real and simply a figment of the human imagination. Maya means that the world is not as it seems; the world that one experiences is misleading as far as its true nature is concerned.'[135] According to Wendy Doniger, 'to say that the universe is an illusion (māyā) is not to say that it is unreal; it is to say, instead, that it is not what it seems to be, that it is something constantly being made. Māyā not only deceives people about the things they think they know; more basically, it limits their knowledge.'[136]

In the Upanishads, Māyā is the perceived changing reality and it co-exists with Brahman which is the hidden true reality.[137][138]Maya, or 'illusion', is an important idea in the Upanishads, because the texts assert that in the human pursuit of blissful and liberating self-knowledge, it is Maya which obscures, confuses and distracts an individual.[139][140]

Schools of Vedanta[edit]

The Upanishads form one of the three main sources for all schools of Vedanta, together with the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahmasutras.[141] Due to the wide variety of philosophical teachings contained in the Upanishads, various interpretations could be grounded on the Upanishads. The schools of Vedānta seek to answer questions about the relation between atman and Brahman, and the relation between Brahman and the world.[142] The schools of Vedanta are named after the relation they see between atman and Brahman:[143]

- According to Advaita Vedanta, there is no difference.[143]

- According to Vishishtadvaita the jīvātman is a part of Brahman, and hence is similar, but not identical.

- According to Dvaita, all individual souls (jīvātmans) and matter as eternal and mutually separate entities.

Other schools of Vedanta include Nimbarka's Dvaitadvaita, Vallabha's Suddhadvaita and Chaitanya's Acintya Bhedabheda.[144] The philosopher Adi Sankara has provided commentaries on 11 mukhya Upanishads.[145]

Advaita Vedanta[edit]

Advaita literally means non-duality, and it is a monistic system of thought.[146] It deals with the non-dual nature of Brahman and Atman. Advaita is considered the most influential sub-school of the Vedanta school of Hindu philosophy.[146] Gaudapada was the first person to expound the basic principles of the Advaita philosophy in a commentary on the conflicting statements of the Upanishads.[147] Gaudapada's Advaita ideas were further developed by Shankara (8th century CE).[148][149] King states that Gaudapada's main work, Māṇḍukya Kārikā, is infused with philosophical terminology of Buddhism, and uses Buddhist arguments and analogies.[150] King also suggests that there are clear differences between Shankara's writings and the Brahmasutra,[148][149] and many ideas of Shankara are at odds with those in the Upanishads.[151] Radhakrishnan, on the other hand, suggests that Shankara's views of Advaita were straightforward developments of the Upanishads and the Brahmasutra,[152] and many ideas of Shankara derive from the Upanishads.[153]

Shankara in his discussions of the Advaita Vedanta philosophy referred to the early Upanishads to explain the key difference between Hinduism and Buddhism, stating that Hinduism asserts that Atman (soul, self) exists, whereas Buddhism asserts that there is no soul, no self.[154][155][156]

The Upanishads contain four sentences, the Mahāvākyas (Great Sayings), which were used by Shankara to establish the identity of Atman and Brahman as scriptural truth:

- 'Prajñānam brahma' - 'Consciousness is Brahman' (Aitareya Upanishad)[157]

- 'Aham brahmāsmi' - 'I am Brahman' (Brihadaranyaka Upanishad)[158]

- 'Tat tvam asi' - 'That Thou art' (Chandogya Upanishad)[159]

- 'Ayamātmā brahma' - 'This Atman is Brahman' (Mandukya Upanishad)[160]

Although there are a wide variety of philosophical positions propounded in the Upanishads, commentators since Adi Shankara have usually followed him in seeing idealistmonism as the dominant force.[161][note 12]

Vishishtadvaita[edit]

The second school of Vedanta is the Vishishtadvaita, which was founded by Sri Ramanuja (1017–1137 CE). Sri Ramanuja disagreed with Adi Shankara and the Advaita school.[162] Visistadvaita is a synthetic philosophy bridging the monistic Advaita and theistic Dvaita systems of Vedanta.[163] Sri Ramanuja frequently cited the Upanishads, and stated that Vishishtadvaita is grounded in the Upanishads.[164][165]

Vedas In English Pdf

Sri Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita interpretation of the Upanishad is a qualified monism.[166][167] Sri Ramanuja interprets the Upanishadic literature to be teaching a body-soul theory, states Jeaneane Fowler – a professor of Philosophy and Religious Studies, where the Brahman is the dweller in all things, yet also distinct and beyond all things, as the soul, the inner controller, the immortal.[165] The Upanishads, according to the Vishishtadvaita school, teach individual souls to be of the same quality as the Brahman, but quantitatively they are distinct.[168][169][170]

In the Vishishtadvaita school, the Upanishads are interpreted to be teaching an Ishwar (Vishnu), which is the seat of all auspicious qualities, with all of the empirically perceived world as the body of God who dwells in everything.[165] The school recommends a devotion to godliness and constant remembrance of the beauty and love of personal god. This ultimately leads one to the oneness with abstract Brahman.[171][172][173] The Brahman in the Upanishads is a living reality, states Fowler, and 'the Atman of all things and all beings' in Sri Ramanuja's interpretation.[165]

Dvaita[edit]

The third school of Vedanta called the Dvaita school was founded by Madhvacharya (1199–1278 CE).[174] It is regarded as a strongly theistic philosophic exposition of Upanishads.[163] Madhvacharya, much like Adi Shankara claims for Advaita, and Sri Ramanuja claims for Vishishtadvaita, states that his theistic Dvaita Vedanta is grounded in the Upanishads.[164]

According to the Dvaita school, states Fowler, the 'Upanishads that speak of the soul as Brahman, speak of resemblance and not identity'.[175] Madhvacharya interprets the Upanishadic teachings of the self becoming one with Brahman, as 'entering into Brahman', just like a drop enters an ocean. This to the Dvaita school implies duality and dependence, where Brahman and Atman are different realities. Brahman is a separate, independent and supreme reality in the Upanishads, Atman only resembles the Brahman in limited, inferior, dependent manner according to Madhvacharya.[175][176][177]

Sri Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita school and Shankara's Advaita school are both nondualism Vedanta schools,[171] both are premised on the assumption that all souls can hope for and achieve the state of blissful liberation; in contrast, Madhvacharya believed that some souls are eternally doomed and damned.[178][179]

Similarities with Platonic thought[edit]

Several scholars have recognised parallels between the philosophy of Pythagoras and Plato and that of the Upanishads, including their ideas on sources of knowledge, concept of justice and path to salvation, and Plato's allegory of the cave. Platonic psychology with its divisions of reason, spirit and appetite, also bears resemblance to the three gunas in the Indian philosophy of Samkhya.[180][181][note 13]

Various mechanisms for such a transmission of knowledge have been conjectured including Pythagoras traveling as far as India; Indian philosophers visiting Athens and meeting Socrates; Plato encountering the ideas when in exile in Syracuse; or, intermediated through Persia.[180][183]

However, other scholars, such as Arthur Berriedale Keith, J. Burnet and A. R. Wadia, believe that the two systems developed independently. They note that there is no historical evidence of the philosophers of the two schools meeting, and point out significant differences in the stage of development, orientation and goals of the two philosophical systems. Wadia writes that Plato's metaphysics were rooted in this life and his primary aim was to develop an ideal state.[181] In contrast, Upanishadic focus was the individual, the self (atman, soul), self-knowledge, and the means of an individual's moksha (freedom, liberation in this life or after-life).[184][11][185]

Translations[edit]

The Upanishads have been translated into various languages including Persian, Italian, Urdu, French, Latin, German, English, Dutch, Polish, Japanese, Spanish and Russian.[186] The Moghul Emperor Akbar's reign (1556–1586) saw the first translations of the Upanishads into Persian.[187][188] His great-grandson, Sultan Mohammed Dara Shikoh, produced a collection called Oupanekhat in 1656, wherein 50 Upanishads were translated from Sanskrit into Persian.[189]

Anquetil Duperron, a French Orientalist received a manuscript of the Oupanekhat and translated the Persian version into French and Latin, publishing the Latin translation in two volumes in 1801–1802 as Oupneck'hat.[189][187] The French translation was never published.[190] The Latin version was the initial introduction of Upanishadic thought to Western scholars.[191] However, according to Deussen, the Persian translators took great liberties in translating the text and at times changed the meaning.[192]

The first Sanskrit to English translation of the Aitareya Upanishad was made by Colebrooke,[193] in 1805 and the first English translation of the Kena Upanishad was made by Rammohun Roy in 1816.[194][195]

The first German translation appeared in 1832 and Roer's English version appeared in 1853. However, Max Mueller's 1879 and 1884 editions were the first systematic English treatment to include the 12 Principal Upanishads.[186] Other major translations of the Upanishads have been by Robert Ernest Hume (13 Principal Upanishads),[196]Paul Deussen (60 Upanishads),[197]Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (18 Upanishads),[198] and Patrick Olivelle (32 Upanishads in two books).[199][161] Olivelle's translation won the 1998 A.K. Ramanujan Book Prize for Translation.[200]

Reception in the West[edit]

The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer read the Latin translation and praised the Upanishads in his main work, The World as Will and Representation (1819), as well as in his Parerga and Paralipomena (1851).[201] He found his own philosophy was in accord with the Upanishads, which taught that the individual is a manifestation of the one basis of reality. For Schopenhauer, that fundamentally real underlying unity is what we know in ourselves as 'will'. Schopenhauer used to keep a copy of the Latin Oupnekhet by his side and commented,

It has been the solace of my life, it will be the solace of my death.[202]

Another German philosopher, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, praised the ideas in the Upanishads,[203] as did others.[204] In the United States, the group known as the Transcendentalists were influenced by the German idealists. Americans, such as Emerson and Thoreau embraced Schelling's interpretation of Kant's Transcendental idealism, as well as his celebration of the romantic, exotic, mystical aspect of the Upanishads. As a result of the influence of these writers, the Upanishads gained renown in Western countries.[205]

The poet T. S. Eliot, inspired by his reading of the Upanishads, based the final portion of his famous poem The Waste Land (1922) upon one of its verses.[206] According to Eknath Easwaran, the Upanishads are snapshots of towering peaks of consciousness.[207]

Juan Mascaró, a professor at the University of Barcelona and a translator of the Upanishads, states that the Upanishads represents for the Hindu approximately what the New Testament represents for the Christian, and that the message of the Upanishads can be summarized in the words, 'the kingdom of God is within you'.[208]

Paul Deussen in his review of the Upanishads, states that the texts emphasize Brahman-Atman as something that can be experienced, but not defined.[209] This view of the soul and self are similar, states Deussen, to those found in the dialogues of Plato and elsewhere. The Upanishads insisted on oneness of soul, excluded all plurality, and therefore, all proximity in space, all succession in time, all interdependence as cause and effect, and all opposition as subject and object.[209] Max Müller, in his review of the Upanishads, summarizes the lack of systematic philosophy and the central theme in the Upanishads as follows,

There is not what could be called a philosophical system in these Upanishads. They are, in the true sense of the word, guesses at truth, frequently contradicting each other, yet all tending in one direction. The key-note of the old Upanishads is 'know thyself,' but with a much deeper meaning than that of the γνῶθι σεαυτόν of the Delphic Oracle. The 'know thyself' of the Upanishads means, know thy true self, that which underlines thine Ego, and find it and know it in the highest, the eternal Self, the One without a second, which underlies the whole world.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^The shared concepts include rebirth, samsara, karma, meditation, renunciation and moksha.[4]

- ^The Upanishadic, Buddhist and Jain renunciation traditions form parallel traditions, which share some common concepts and interests. While Kuru-Panchala, at the central Ganges Plain, formed the center of the early Upanishadic tradition, Kosala-Magadha at the central Ganges Plain formed the center of the other shramanic traditions.[5]

- ^Advaita Vedanta, summarized by Shankara (788–820), advances a non-dualistic (a-dvaita) interpretation of the Upanishads.'[13]

- ^'These Upanishadic ideas are developed into Advaita monism. Brahman's unity comes to be taken to mean that appearances of individualities.[14]

- ^'The doctrine of advaita (non dualism) has its origin in the Upanishads.'

- ^The pre-Buddhist Upanishads are: Brihadaranyaka, Chandogya, Kaushitaki, Aitareya, and Taittiriya Upanishads.[18]

- ^These are believed to pre-date Gautam Buddha (c. 500 BCE)[65]

- ^The Muktika manuscript found in colonial era Calcutta is the usual default, but other recensions exist.

- ^ abSome scholars list ten as principal, while most consider twelve or thirteen as principal mukhya Upanishads.[80][81][82]

- ^Parmeshwaranand classifies Maitrayani with Samaveda, most scholars with Krishna Yajurveda[77][88]

- ^Oliville: 'In this Introduction I have avoided speaking of 'the philosophy of the upanishads', a common feature of most introductions to their translations. These documents were composed over several centuries and in various regions, and it is futile to try to discover a single doctrine or philosophy in them.'[93]

- ^According to Collins, the breakdown of the Vedic cults is more obscured by retrospective ideology than any other period in Indian history. It is commonly assumed that the dominant philosophy now became an idealist monism, the identification of atman (self) and Brahman (Spirit), and that this mysticism was believed to provide a way to transcend rebirths on the wheel of karma. This is far from an accurate picture of what we read in the Upanishads. It has become traditional to view the Upanishads through the lens of Shankara's Advaita interpretation. This imposes the philosophical revolution of about 700 C.E. upon a very different situation 1,000 to 1,500 years earlier. Shankara picked out monist and idealist themes from a much wider philosophical lineup.[151]

- ^For instances of Platonic pluralism in the early Upanishads see Randall.[182]

References[edit]

- ^'Upanishad'. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ abWendy Doniger (1990), Textual Sources for the Study of Hinduism, 1st Edition, University of Chicago Press, ISBN978-0226618470, pages 2-3; Quote: 'The Upanishads supply the basis of later Hindu philosophy; they are widely known and quoted by most well-educated Hindus, and their central ideas have also become a part of the spiritual arsenal of rank-and-file Hindus.'

- ^Wiman Dissanayake (1993), Self as Body in Asian Theory and Practice (Editors: Thomas P. Kasulis et al), State University of New York Press, ISBN978-0791410806, page 39; Quote: 'The Upanishads form the foundations of Hindu philosophical thought and the central theme of the Upanishads is the identity of Atman and Brahman, or the inner self and the cosmic self.';

Michael McDowell and Nathan Brown (2009), World Religions, Penguin, ISBN978-1592578467, pages 208-210 - ^Olivelle 1998, pp. xx-xxiv.

- ^Samuel 2010.

- ^Patrick Olivelle 1998, pp. 3-4.

- ^Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanisads, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0195352429, page 3; Quote: 'Even though theoretically the whole of vedic corpus is accepted as revealed truth [shruti], in reality it is the Upanishads that have continued to influence the life and thought of the various religious traditions that we have come to call Hindu. Upanishads are the scriptures par excellence of Hinduism'.

- ^Max Müller, The Upanishads, Part 1, Oxford University Press, page LXXXVI footnote 1

- ^ abMahadevan 1956, p. 59.

- ^ abcPT Raju (1985), Structural Depths of Indian Thought, State University of New York Press, ISBN978-0887061394, pages 35-36

- ^ abcWD Strappini, The Upanishads, p. 258, at Google Books, The Month and Catholic Review, Vol. 23, Issue 42

- ^Ranade 1926, p. 205.

- ^Cornille 1992, p. 12.

- ^Phillips 1995, p. 10.

- ^ abcStephen Phillips (2009), Yoga, Karma, and Rebirth: A Brief History and Philosophy, Columbia University Press, ISBN978-0231144858, pages 25-29 and Chapter 1

- ^E Easwaran (2007), The Upanishads, ISBN978-1586380212, pages 298-299

- ^ abMahadevan 1956, p. 56.

- ^ abcdefghPatrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0195124354, pages 12-14

- ^ abcdKing 1995, p. 52.

- ^ abcdeOlivelle 1992, pp. 5, 8–9.

- ^ abcFlood 1996, p. 96.

- ^Ranade 1926, p. 12.

- ^ abVarghese 2008, p. 101.

- ^Clarke, John James (1997). Oriental enlightenment. Routledge. p. 68. ISBN978-0-415-13376-0.

- ^Deussen 2010, p. 42, Quote: 'Here we have to do with the Upanishads, and the world-wide historical significance of these documents cannot, in our judgement, be more clearly indicated than by showing how the deep fundamental conception of Plato and Kant was precisely that which already formed the basis of Upanishad teaching'..

- ^Lawrence Hatab (1982). R. Baine Harris (ed.). Neoplatonism and Indian Thought. State University of New York Press. pp. 31–38. ISBN978-0-87395-546-1.;

Paulos Gregorios (2002). Neoplatonism and Indian Philosophy. State University of New York Press. pp. 71–79, 190–192, 210–214. ISBN978-0-7914-5274-5. - ^Ben-Ami Scharfstein (1998). A Comparative History of World Philosophy: From the Upanishads to Kant. State University of New York Press. pp. 62–74. ISBN978-0-7914-3683-7.

- ^'Upanishad'. Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^Jones, Constance (2007). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. New York: Infobase Publishing. p. 472. ISBN0816073368.

- ^Monier-Williams, p. 201.

- ^Max Müller, Chandogya Upanishad 1.13.4, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, page 22

- ^Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN978-8120814684, page 85

- ^Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 1.13.4, Oxford University Press, page 190

- ^Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0195124354, page 185

- ^ abS Radhakrishnan, The Principal Upanishads George Allen & Co., 1951, pages 22, Reprinted as ISBN978-8172231248

- ^Vaman Shivaram Apte, The Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary, see apauruSeya

- ^D Sharma, Classical Indian Philosophy: A Reader, Columbia University Press, ISBN , pages 196-197

- ^Jan Westerhoff (2009), Nagarjuna's Madhyamaka: A Philosophical Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0195384963, page 290

- ^Warren Lee Todd (2013), The Ethics of Śaṅkara and Śāntideva: A Selfless Response to an Illusory World, ISBN978-1409466819, page 128

- ^Hartmut Scharfe (2002), Handbook of Oriental Studies, BRILL Academic, ISBN978-9004125568, pages 13-14

- ^Pattanaik, Devdutt (2013). Sita: An Illustrated Retelling of the Ramayana. India: Penguin Books. pp. 19–22. ISBN9780143064329.

- ^Mahadevan 1956, pp. 59-60.

- ^Ellison Findly (1999), Women and the Arahant Issue in Early Pali Literature, Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, Vol. 15, No. 1, pages 57-76

- ^Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN978-8120814684, pages 301-304

- ^For example, see: Kaushitaki Upanishad Robert Hume (Translator), Oxford University Press, page 306 footnote 2

- ^Max Müller, The Upanishads, p. PR72, at Google Books, Oxford University Press, page LXXII

- ^Patrick Olivelle (1998), Unfaithful Transmitters, Journal of Indian Philosophy, April 1998, Volume 26, Issue 2, pages 173-187;

Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0195124354, pages 583-640 - ^WD Whitney, The Upanishads and Their Latest Translation, The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 7, No. 1, pages 1-26;

F Rusza (2010), The authorlessness of the philosophical sūtras, Acta Orientalia, Volume 63, Number 4, pages 427-442 - ^Mark Juergensmeyer et al. (2011), Encyclopedia of Global Religion, SAGE Publications, ISBN978-0761927297, page 1122

- ^ abcOlivelle 1998, pp. 12-13.

- ^Olivelle 1998, p. xxxvi.

- ^Patrick Olivelle, Upanishads, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^Olivelle 1998, p. xxxvii.

- ^Olivelle 1998, p. xxxviii.

- ^Olivelle 1998, p. xxxix.

- ^Deussen 1908, pp. 35–36.

- ^Tripathy 2010, p. 84.

- ^Sen 1937, p. 19.

- ^Ayyangar, T. R. Srinivasa (1941). The Samanya-Vedanta Upanisads. Jain Publishing (Reprint 2007). ISBN978-0895819833. OCLC27193914.

- ^Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997, pp. 556-568.

- ^Holdrege 1995, pp. 426.

- ^Srinivasan, Doris (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes. BRILL Academic. pp. 112–120. ISBN978-9004107588.

- ^Ayyangar, TRS (1953). Saiva Upanisads. Jain Publishing Co. (Reprint 2007). pp. 194–196. ISBN978-0895819819.

- ^M. Fujii, On the formation and transmission of the JUB, Harvard Oriental Series, Opera Minora 2, 1997

- ^Olivelle 1998, pp. 3–4.

- ^Ranade 1926, p. 61.

- ^Joshi 1994, pp. 90–92.

- ^Heehs 2002, p. 85.

- ^Lal 1992, p. 4090.

- ^Rinehart 2004, p. 17.

- ^Singh 2002, pp. 3–4.

- ^ abSchrader & Adyar Library 1908, p. v.

- ^ abcdefgOlivelle 1998, pp. xxxii-xxxiii.

- ^Paul Deussen (1966), The Philosophy of the Upanishads, Dover, ISBN978-0486216164, pages 283-296; for an example, see Garbha Upanishad

- ^ abPatrick Olivelle (1992), The Samnyasa Upanisads, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0195070453, pages 1-12, 98-100; for an example, see Bhikshuka Upanishad

- ^Brooks 1990, pp. 13–14.

- ^ abcdParmeshwaranand 2000, pp. 404–406.

- ^Paul Deussen (2010 Reprint), Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN978-8120814691, pages 566-568

- ^ abPeter Heehs (2002), Indian Religions, New York University Press, ISBN978-0814736500, pages 60-88

- ^Robert C Neville (2000), Ultimate Realities, SUNY Press, ISBN978-0791447765, page 319

- ^ abStephen Phillips (2009), Yoga, Karma, and Rebirth: A Brief History and Philosophy, Columbia University Press, ISBN978-0231144858, pages 28-29

- ^Olivelle 1998, p. xxiii.

- ^ abPatrick Olivelle (1992), The Samnyasa Upanisads, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0195070453, pages x-xi, 5

- ^ abThe Yoga Upanishads TR Srinivasa Ayyangar (Translator), SS Sastri (Editor), Adyar Library

- ^AM Sastri, The Śākta Upaniṣads, with the commentary of Śrī Upaniṣad-Brahma-Yogin, Adyar Library, OCLC7475481

- ^AM Sastri, The Vaishnava-upanishads: with the commentary of Sri Upanishad-brahma-yogin, Adyar Library, OCLC83901261

- ^AM Sastri, The Śaiva-Upanishads with the commentary of Sri Upanishad-Brahma-Yogin, Adyar Library, OCLC863321204

- ^Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN978-8120814684, pages 217-219

- ^Prāṇāgnihotra is missing in some anthologies, included by Paul Deussen (2010 Reprint), Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN978-8120814691, page 567

- ^Atharvasiras is missing in some anthologies, included by Paul Deussen (2010 Reprint), Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN978-8120814691, page 568

- ^Glucklich 2008, p. 70.

- ^Fields 2001, p. 26.

- ^ abOlivelle 1998, p. 4.

- ^S Radhakrishnan, The Principal Upanishads George Allen & Co., 1951, pages 17-19, Reprinted as ISBN978-8172231248

- ^Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli, The Principal Upanishads, Indus / Harper Collins India; 5th edition (1994), ISBN978-8172231248

- ^S Radhakrishnan, The Principal Upanishads George Allen & Co., 1951, pages 19-20, Reprinted as ISBN978-8172231248

- ^S Radhakrishnan, The Principal Upanishads George Allen & Co., 1951, page 24, Reprinted as ISBN978-8172231248

- ^Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN978-8120814684, pages 114-115 with preface and footnotes;

Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 3.17, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 212-213 - ^Henk Bodewitz (1999), Hindu Ahimsa, in Violence Denied (Editors: Jan E. M. Houben, et al), Brill, ISBN978-9004113442, page 40

- ^PV Kane, Samanya Dharma, History of Dharmasastra, Vol. 2, Part 1, page 5

- ^Chatterjea, Tara. Knowledge and Freedom in Indian Philosophy. Oxford: Lexington Books. p. 148.

- ^Tull, Herman W. The Vedic Origins of Karma: Cosmos as Man in Ancient Indian Myth and Ritual. SUNY Series in Hindu Studies. P. 28

- ^ abcdMahadevan 1956, p. 57.

- ^Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN978-8120814684, pages 30-42;

- ^ abMax Müller (1962), Manduka Upanishad, in The Upanishads - Part II, Oxford University Press, Reprinted as ISBN978-0486209937, pages 30-33

- ^Eduard Roer, Mundaka Upanishad[permanent dead link] Bibliotheca Indica, Vol. XV, No. 41 and 50, Asiatic Society of Bengal, pages 153-154

- ^Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN978-8120814684, pages 331-333

- ^'laid those fires' is a phrase in Vedic literature that implies yajna and related ancient religious rituals; see Maitri Upanishad - Sanskrit Text with English Translation[permanent dead link] EB Cowell (Translator), Cambridge University, Bibliotheca Indica, First Prapathaka

- ^Max Müller, The Upanishads, Part 2, Maitrayana-Brahmana Upanishad, Oxford University Press, pages 287-288

- ^Hume, Robert Ernest (1921), The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pp. 412–414

- ^Hume, Robert Ernest (1921), The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pp. 428–429

- ^Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN978-8120814684, pages 350-351

- ^ abPaul Deussen, The Philosophy of Upanishads at Google Books, University of Kiel, T&T Clark, pages 342-355, 396-412

- ^RC Mishra (2013), Moksha and the Hindu Worldview, Psychology & Developing Societies, Vol. 25, No. 1, pages 21-42

- ^Mark B. Woodhouse (1978), Consciousness and Brahman-Atman, The Monist, Vol. 61, No. 1, Conceptions of the Self: East & West (JANUARY, 1978), pages 109-124

- ^ abcJayatilleke 1963, p. 32.

- ^Jayatilleke 1963, pp. 36-39.

- ^ abJames Lochtefeld, Brahman, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M, Rosen Publishing. ISBN978-0823931798, page 122

- ^ ab[a] Richard King (1995), Early Advaita Vedanta and Buddhism, State University of New York Press, ISBN978-0791425138, page 64, Quote: 'Atman as the innermost essence or soul of man, and Brahman as the innermost essence and support of the universe. (...) Thus we can see in the Upanishads, a tendency towards a convergence of microcosm and macrocosm, culminating in the equating of Atman with Brahman'.

[b] Chad Meister (2010), The Oxford Handbook of Religious Diversity, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0195340136, page 63; Quote: 'Even though Buddhism explicitly rejected the Hindu ideas of Atman ('soul') and Brahman, Hinduism treats Sakyamuni Buddha as one of the ten avatars of Vishnu.'

[c] David Lorenzen (2004), The Hindu World (Editors: Sushil Mittal and Gene Thursby), Routledge, ISBN0-415215277, pages 208-209, Quote: 'Advaita and nirguni movements, on the other hand, stress an interior mysticism in which the devotee seeks to discover the identity of individual soul (atman) with the universal ground of being (brahman) or to find god within himself'. - ^PT Raju (2006), Idealistic Thought of India, Routledge, ISBN978-1406732627, page 426 and Conclusion chapter part XII

- ^Mariasusai Dhavamony (2002), Hindu-Christian Dialogue: Theological Soundings and Perspectives, Rodopi Press, ISBN978-9042015104, pages 43-44

- ^For dualism school of Hinduism, see: Francis X. Clooney (2010), Hindu God, Christian God: How Reason Helps Break Down the Boundaries between Religions, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0199738724, pages 51-58, 111-115;

For monist school of Hinduism, see: B Martinez-Bedard (2006), Types of Causes in Aristotle and Sankara, Thesis - Department of Religious Studies (Advisors: Kathryn McClymond and Sandra Dwyer), Georgia State University, pages 18-35 - ^Jeffrey Brodd (2009), World Religions: A Voyage of Discovery, Saint Mary's Press, ISBN978-0884899976, pages 43-47

- ^Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN978-8120814684, page 91

- ^[a]Atman, Oxford Dictionaries, Oxford University Press (2012), Quote: '1. real self of the individual; 2. a person's soul';

[b] John Bowker (2000), The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0192800947, See entry for Atman;

[c] WJ Johnson (2009), A Dictionary of Hinduism, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0198610250, See entry for Atman (self). - ^Soul is synonymous with self in translations of ancient texts of Hindu philosophy

- ^Alice Bailey (1973), The Soul and Its Mechanism, ISBN978-0853301158, pages 82-83

- ^Eknath Easwaran (2007), The Upanishads, Nilgiri Press, ISBN978-1586380212, pages 38-39, 318-320

- ^ abJohn Koller (2012), Shankara, in Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion, (Editors: Chad Meister, Paul Copan), Routledge, ISBN978-0415782944, pages 99-102

- ^Paul Deussen, The Philosophy of the Upanishads at Google Books, Dover Publications, pages 86-111, 182-212

- ^Nakamura (1990), A History of Early Vedanta Philosophy', p.500. Motilall Banarsidas

- ^Mahadevan 1956, pp. 62-63.

- ^Paul Deussen, The Philosophy of the Upanishads, p. 161, at Google Books, pages 161, 240-254

- ^Ben-Ami Scharfstein (1998), A Comparative History of World Philosophy: From the Upanishads to Kant, State University of New York Press, ISBN978-0791436844, page 376

- ^H.M. Vroom (1996), No Other Gods, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN978-0802840974, page 57

- ^Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty (1986), Dreams, Illusion, and Other Realities, University of Chicago Press, ISBN978-0226618555, page 119

- ^Archibald Edward Gough (2001), The Philosophy of the Upanishads and Ancient Indian Metaphysics, Routledge, ISBN978-0415245227, pages 47-48

- ^Teun Goudriaan (2008), Maya: Divine And Human, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN978-8120823891, pages 1-17

- ^KN Aiyar (Translator, 1914), Sarvasara Upanishad, in Thirty Minor Upanishads, page 17, OCLC6347863

- ^Adi Shankara, Commentary on Taittiriya Upanishad at Google Books, SS Sastri (Translator), Harvard University Archives, pages 191-198

- ^Radhakrishnan 1956, p. 272.

- ^Raju 1992, p. 176-177.

- ^ abRaju 1992, p. 177.

- ^Ranade 1926, pp. 179–182.

- ^Mahadevan 1956, p. 63.

- ^ abEncyclopædia Britannica.

- ^Radhakrishnan 1956, p. 273.

- ^ abKing 1999, p. 221.

- ^ abNakamura 2004, p. 31.

- ^King 1999, p. 219.

- ^ abCollins 2000, p. 195.

- ^Radhakrishnan 1956, p. 284.

- ^John Koller (2012), Shankara in Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion (Editors: Chad Meister, Paul Copan), Routledge, ISBN978-0415782944, pages 99-108

- ^Edward Roer (translator), Shankara's Introduction, p. 3, at Google Books to Brihad Aranyaka Upanishad at pages 3-4; Quote - '(...) Lokayatikas and Bauddhas who assert that the soul does not exist. There are four sects among the followers of Buddha: 1. Madhyamicas who maintain all is void; 2. Yogacharas, who assert except sensation and intelligence all else is void; 3. Sautranticas, who affirm actual existence of external objects no less than of internal sensations; 4. Vaibhashikas, who agree with later (Sautranticas) except that they contend for immediate apprehension of exterior objects through images or forms represented to the intellect.'

- ^Edward Roer (Translator), Shankara's Introduction, p. 3, at Google Books to Brihad Aranyaka Upanishad at page 3, OCLC19373677

- ^KN Jayatilleke (2010), Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge, ISBN978-8120806191, pages 246-249, from note 385 onwards;

Steven Collins (1994), Religion and Practical Reason (Editors: Frank Reynolds, David Tracy), State Univ of New York Press, ISBN978-0791422175, page 64; Quote: 'Central to Buddhist soteriology is the doctrine of not-self (Pali: anattā, Sanskrit: anātman, the opposed doctrine of ātman is central to Brahmanical thought). Put very briefly, this is the [Buddhist] doctrine that human beings have no soul, no self, no unchanging essence.';

Edward Roer (Translator), Shankara's Introduction, p. 2, at Google Books, pages 2-4

Katie Javanaud (2013), Is The Buddhist 'No-Self' Doctrine Compatible With Pursuing Nirvana?, Philosophy Now;

John C. Plott et al (2000), Global History of Philosophy: The Axial Age, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN978-8120801585, page 63, Quote: 'The Buddhist schools reject any Ātman concept. As we have already observed, this is the basic and ineradicable distinction between Hinduism and Buddhism'. - ^Panikkar 2001, p. 669.

- ^Panikkar 2001, pp. 725–727.

- ^Panikkar 2001, pp. 747–750.

- ^Panikkar 2001, pp. 697–701.

- ^ abOlivelle 1998.

- ^Klostermaier 2007, pp. 361–363.

- ^ abChari 1956, p. 305.

- ^ abStafford Betty (2010), Dvaita, Advaita, and Viśiṣṭādvaita: Contrasting Views of Mokṣa, Asian Philosophy, Vol. 20, No. 2, pages 215-224, doi:10.1080/09552367.2010.484955

- ^ abcdJeaneane D. Fowler (2002). Perspectives of Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Hinduism. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 298–299, 320–321, 331 with notes. ISBN978-1-898723-93-6.

- ^William M. Indich (1995). Consciousness in Advaita Vedanta. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 1–2, 97–102. ISBN978-81-208-1251-2.

- ^Bruce M. Sullivan (2001). The A to Z of Hinduism. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 239. ISBN978-0-8108-4070-6.

- ^Stafford Betty (2010), Dvaita, Advaita, and Viśiṣṭādvaita: Contrasting Views of Mokṣa, Asian Philosophy: An International Journal of the Philosophical Traditions of the East, Volume 20, Issue 2, pages 215-224

- ^Edward Craig (2000), Concise Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Routledge, ISBN978-0415223645, pages 517-518

- ^Sharma, Chandradhar (1994). A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 373–374. ISBN81-208-0365-5.

- ^ abJ.A.B. van Buitenen (2008), Ramanuja - Hindu theologian and Philosopher, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^Jon Paul Sydnor (2012). Ramanuja and Schleiermacher: Toward a Constructive Comparative Theology. Casemate. pp. 20–22 with footnote 32. ISBN978-0227680247.

- ^Joseph P. Schultz (1981). Judaism and the Gentile Faiths: Comparative Studies in Religion. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 81–84. ISBN978-0-8386-1707-6.

- ^Raghavendrachar 1956, p. 322.

- ^ abJeaneane D. Fowler (2002). Perspectives of Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Hinduism. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 356–357. ISBN978-1-898723-93-6.

- ^Stoker, Valerie (2011). 'Madhva (1238-1317)'. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^Bryant, Edwin (2007). Krishna : A Sourcebook (Chapter 15 by Deepak Sarma). Oxford University Press. pp. 358–359. ISBN978-0195148923.

- ^Sharma, Chandradhar (1994). A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 374–375. ISBN81-208-0365-5.

- ^Bryant, Edwin (2007). Krishna : A Sourcebook (Chapter 15 by Deepak Sarma). Oxford University Press. pp. 361–362. ISBN978-0195148923.

- ^ abChousalkar 1986, pp. 130-134.

- ^ abWadia 1956, p. 64-65.

- ^Collins 2000, pp. 197–198.

- ^Urwick 1920.

- ^Keith 2007, pp. 602-603.

- ^RC Mishra (2013), Moksha and the Hindu Worldview, Psychology & Developing Societies, Vol. 25, No. 1, pages 21-42; Chousalkar, Ashok (1986), Social and Political Implications of Concepts Of Justice And Dharma, pages 130-134

- ^ abSharma 1985, p. 20.

- ^ abMüller 1900, p. lvii.

- ^Müller 1899, p. 204.

- ^ abDeussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997, pp. 558-59.

- ^Müller 1900, p. lviii.

- ^Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997, pp. 558-559.

- ^Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997, pp. 915-916.

- ^See Henry Thomas Colebrooke (1858), Essays on the religion and philosophy of the Hindus. London: Williams and Norgate. In this volume, see chapter 1 (pp. 1–69), On the Vedas, or Sacred Writings of the Hindus, reprinted from Colebrooke's Asiatic Researches, Calcutta: 1805, Vol 8, pp. 369–476. A translation of the Aitareya Upanishad appears in pages 26–30 of this chapter.

- ^Zastoupil, L (2010). Rammohun Roy and the Making of Victorian Britain, By Lynn Zastoupil. ISBN9780230111493. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^'The Upanishads, Part 1, by Max Müller'.

- ^Hume, Robert Ernest (1921), The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press

- ^Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997.

- ^Radhakrishnan, Sarvapalli (1953), The Principal Upanishads, New Delhi: HarperCollins Publishers (1994 Reprint), ISBN81-7223-124-5

- ^Olivelle 1992.

- ^'AAS SAC A.K. Ramanujan Book Prize for Translation'. Association of Asian Studies. 25 June 2002. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^Schopenhauer & Payne 2000, p. 395.

- ^Schopenhauer & Payne 2000, p. 397.

- ^Herman Wayne Tull (1989). The Vedic Origins of Karma: Cosmos as Man in Ancient Indian Myth and Ritual. State University of New York Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN978-0-7914-0094-4.

- ^Klaus G. Witz (1998). The Supreme Wisdom of the Upaniṣads: An Introduction. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 35–44. ISBN978-81-208-1573-5.

- ^Versluis 1993, pp. 69, 76, 95. 106–110.

- ^Eliot 1963.

- ^Easwaran 2007, p. 9.

- ^Juan Mascaró, The Upanishads, Penguin Classics, ISBN978-0140441635, page 7, 146, cover

- ^ abPaul Deussen, The Philosophy of the Upanishads University of Kiel, T&T Clark, pages 150-179

Sources[edit]

- Brooks, Douglas Renfrew (1990), The Secret of the Three Cities: An Introduction to Hindu Shakta Tantrism, The University of Chicago Press

- Brown, Rev. George William (1922), Missionary review of the world, Volume 45, Funk & Wagnalls

- Deussen, Paul; Bedekar, V.M. (tr.); Palsule (tr.), G.B. (1997). Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 2. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN978-81-208-1467-7.

- Deussen, P. (2010), The Philosophy of the Upanishads, Cosimo, ISBN978-1-61640-239-6

- Chari, P. N. Srinivasa (1956), Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (ed.), History of Philosophy Eastern and Western

- Chousalkar, Ashok (1986), Social and Political Implications of Concepts Of Justice And Dharma, Mittal Publications

- Collins, Randall (2000), The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change, Harvard University Press, ISBN0-674-00187-7

- Cornille, Catherine (1992), The Guru in Indian Catholicism: Ambiguity Or Opportunity of Inculturation, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN978-0-8028-0566-9

- Deussen, Paul (1908), The philosophy of the Upanishads, Alfred Shenington Geden, T. & T. Clark, ISBN0-7661-5470-X

- Easwaran, Eknath (2007), The Upanishads, Nilgiri Press, ISBN978-1-58638-021-2

- Eliot, T. S. (1963), Collected Poems, 1909-1962, New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, ISBN0-15-118978-1

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Advaita, retrieved 10 August 2010

- Farquhar, John Nicol (1920). An outline of the religious literature of India. H. Milford, Oxford university press. ISBN81-208-2086-X.

- Fields, Gregory P (2001), Religious Therapeutics: Body and Health in Yoga, Āyurveda, and Tantra, SUNY Press, ISBN0-7914-4916-5

- Flood, Gavin D. (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press, ISBN978-0521438780

- Glucklich, Ariel (2008), The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective, Oxford University Press, ISBN0-19-531405-0

- Heehs, Peter (2002), Indian religions: a historical reader of spiritual expression and experience, NYU Press, ISBN978-0-8147-3650-0

- Holdrege, Barbara A. (1995), Veda and Torah, Albany: SUNY Press, ISBN0-7914-1639-9

- Jayatilleke, K.N. (1963), Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge(PDF) (1st ed.), London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- Joshi, Kireet (1994), The Veda and Indian culture: an introductory essay, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN978-81-208-0889-8

- Keith, Arthur Berriedale (2007). The Religion and Philosophy of the Veda and Upanishads. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN978-81-208-0644-3.

- King, Richard (1999), Indian philosophy: an introduction to Hindu and Buddhist thought, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN0-87840-756-1

- King, Richard (1995), Early Advaita Vedānta and Buddhism: the Mahāyāna context of the Gauḍapādīya-kārikā, Gauḍapāda, State University of New York Press, ISBN978-0-7914-2513-8

- Klostermaier, Klaus K. (2007), A survey of Hinduism, SUNY Press, ISBN0-585-04507-0

- Lanman, Charles R (1897), The Outlook, Volume 56, Outlook Co.

- Lal, Mohan (1992), Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: sasay to zorgot, Sahitya Akademi, ISBN978-81-260-1221-3

- Müller, Friedrich Max (1900), The Upanishads Sacred books of the East The Upanishads, Friedrich Max Müller, Oxford University Press

- Mahadevan, T. M. P (1956), Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (ed.), History of Philosophy Eastern and Western, George Allen & Unwin Ltd

- Monier-Williams, A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, ISBN0-8426-0286-0, retrieved 10 August 2010

- Müller, F. Max (1899), The science of language founded on lectures delivered at the royal institution in 1861 AND 1863, ISBN0-404-11441-5

- Nakamura, Hajime (2004), A history of early Vedānta philosophy, Volume 2, Trevor Leggett, Motilal Banarsidass

- Patrick Olivelle (1998). The Early Upanisads. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0195124354.

- Olivelle, Patrick (1992). The Samnyasa Upanisads. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0195070453.

- Olivelle, Patrick (1998), Upaniṣads, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0192835765

- Panikkar, Raimundo (2001), The Vedic experience: Mantramañjarī : an anthology of the Vedas for modern man and contemporary celebration, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN978-81-208-1280-2

- Parmeshwaranand, Swami (2000), Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Upanisads, Sarup & Sons, ISBN978-81-7625-148-8

- Phillips, Stephen H. (1995), Classical Indian metaphysics: refutations of realism and the emergence of 'new logic', Open Court Publishing, ISBN978-81-208-1489-9, retrieved 24 October 2010

- Samuel, Geoffrey (2010), The Origins of Yoga and Tantra. Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century, Cambridge University Press

- Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli (1956), Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (ed.), History of Philosophy Eastern and Western, George Allen & Unwin Ltd

- Raghavendrachar, Vidvan H. N (1956), Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (ed.), History of Philosophy Eastern and Western

- Ranade, R. D. (1926), A constructive survey of Upanishadic philosophy, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan

- Rinehart, Robin (2004), Robin Rinehart (ed.), Contemporary Hinduism: ritual, culture, and practice, ABC-CLIO, ISBN978-1-57607-905-8

- Schopenhauer, Arthur; Payne, E. F.J (2000), E. F. J. Payne (ed.), Parerga and paralipomena: short philosophical essays, Volume 2 of Parerga and Paralipomena, E. F. J. Payne, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0-19-924221-4

- Schrödinger, Erwin (1992). What is life?. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-42708-1.

- Schrader, Friedrich Otto; Adyar Library (1908), A descriptive catalogue of the Sanskrit manuscripts in the Adyar Library, Oriental Pub. Co

- Sen, Sris Chandra (1937), 'Vedic literature and Upanishads', The Mystic Philosophy of the Upanishads, General Printers & Publishers

- Sharma, B. N. Krishnamurti (2000). A history of the Dvaita school of Vedānta and its literature: from the earliest beginnings to our own times. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN978-81-208-1575-9.

- Sharma, Shubhra (1985), Life in the Upanishads, Abhinav Publications, ISBN978-81-7017-202-4

- Singh, N.K (2002), Encyclopaedia of Hinduism, Anmol Publications PVT. LTD, ISBN978-81-7488-168-7

- Slater, Thomas Ebenezer (1897), Studies in the Upanishads ATLA monograph preservation program, Christian Literature Society for India

- Smith, Huston (1995). The Illustrated World's Religions: A Guide to Our Wisdom Traditions. New York: Labyrinth Publishing. ISBN0-06-067453-9.

- Tripathy, Preeti (2010), Indian religions: tradition, history and culture, Axis Publications, ISBN978-93-80376-17-2

- Urwick, Edward Johns (1920), The message of Plato: a re-interpretation of the 'Republic', Methuen & co. ltd, ISBN9781136231162

- Varghese, Alexander P (2008), India : History, Religion, Vision And Contribution To The World, Volume 1, Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, ISBN978-81-269-0903-2

- Versluis, Arthur (1993), American transcendentalism and Asian religions, Oxford University Press US, ISBN978-0-19-507658-5

- Wadia, A.R. (1956), 'Socrates, Plato and Aristotle', in Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli (ed.), History of Philosophy Eastern and Western, vol. II, George Allen & Unwin Ltd

- Raju, P. T. (1992), The Philosophical Traditions of India, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited

Further reading[edit]

- Edgerton, Franklin (1965). The Beginnings of Indian Philosophy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Embree, Ainslie T. (1966). The Hindu Tradition. New York: Random House. ISBN0-394-71702-3.

- Hume, Robert Ernest. The Thirteen Principal Upanishads. Oxford University Press.

- Johnston, Charles (1898). From the Upanishads. Kshetra Books (Reprinted in 2014). ISBN9781495946530.

- Müller, Max, translator, The Upaniṣads, Part I, New York: Dover Publications (Reprinted in 1962), ISBN0-486-20992-X

- Müller, Max, translator, The Upaniṣads, Part II, New York: Dover Publications (Reprinted in 1962), ISBN0-486-20993-8

- Radhakrishnan, Sarvapalli (1953). The Principal Upanishads. New Delhi: HarperCollins Publishers India (Reprinted in 1994). ISBN81-7223-124-5.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Upanishads |

| Sanskrit Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Complete set of 108 Upanishads, Manuscripts with the commentary of Brahma-Yogin, Adyar Library

- Upanishads, Sanskrit documents in various formats

- The Upaniṣads article in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Theory of 'Soul' in the Upanishads, T. W. Rhys Davids (1899)

- Spinozistic Substance and Upanishadic Self: A Comparative Study, M. S. Modak (1931)

- W. B. Yeats and the Upanishads, A. Davenport (1952)

- The Concept of Self in the Upanishads: An Alternative Interpretation, D. C. Mathur (1972)

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

Divisions |

Rig vedic Sama vedic Yajur vedic Atharva vedic |

| Related Hindu texts |

Brahma puranas Vaishnava puranas Shaiva puranas |

The Vedas (/ˈveɪdəz, ˈviː-/;[1]Sanskrit: वेदveda, 'knowledge') are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute the oldest layer of Sanskrit literature and the oldest scriptures of Hinduism.[2][3] Hindus consider the Vedas to be apauruṣeya, which means 'not of a man, superhuman'[4] and 'impersonal, authorless'.[5][6][7]

Vedas are also called śruti ('what is heard') literature,[8] distinguishing them from other religious texts, which are called smṛti ('what is remembered'). The Veda, for orthodox Indian theologians, are considered revelations seen by ancient sages after intense meditation, and texts that have been more carefully preserved since ancient times.[9][10] In the Hindu Epic the Mahabharata, the creation of Vedas is credited to Brahma.[11] The Vedic hymns themselves assert that they were skillfully created by Rishis (sages), after inspired creativity, just as a carpenter builds a chariot.[10][note 1]

According to tradition, Vyasa is the compiler of the Vedas, who arranged the four kinds of mantras into four Samhitas (Collections).[13][14] There are four Vedas: the Rigveda, the Yajurveda, the Samaveda and the Atharvaveda.[15][16] Each Veda has been subclassified into four major text types – the Samhitas (mantras and benedictions), the Aranyakas (text on rituals, ceremonies, sacrifices and symbolic-sacrifices), the Brahmanas (commentaries on rituals, ceremonies and sacrifices), and the Upanishads (texts discussing meditation, philosophy and spiritual knowledge).[15][17][18] Some scholars add a fifth category – the Upasanas (worship).[19][20]

The various Indian philosophies and denominations have taken differing positions on the Vedas. Schools of Indian philosophy which cite the Vedas as their scriptural authority are classified as 'orthodox' (āstika).[note 2] Other śramaṇa traditions, such as Lokayata, Carvaka, Ajivika, Buddhism and Jainism, which did not regard the Vedas as authorities, are referred to as 'heterodox' or 'non-orthodox' (nāstika) schools.[22][23] Despite their differences, just like the texts of the śramaṇa traditions, the layers of texts in the Vedas discuss similar ideas and concepts.[22]

- 2Chronology

- 3Categories of Vedic texts

- 5Four Vedas

- 5.5Embedded Vedic texts

- 6Post-Vedic literature

Etymology and usage